October is Black History Month in the UK so it feels like a good time to talk about black art. I feel that in writing about this I am treading a very fine line, after all I am not black, and one could argue it is not my history. Yet I believe that it is a history we should all know and acknowledge whatever our colour or race.

Black history month began in the 1920s in the US as an opportunity to share, celebrate and understand the impact of black culture and heritage on all our lives. It was started by Carter F Woodson who was born in Virginia 1875 to enslaved parents. Despite limited access to education he went on to gain a PhD in History from Harvard and worked throughout his life promoting black history in schools. It was as late as 1987 before black history was celebrated here in the UK, 150 years after the abolition of slavery in the Caribbean. Black History Month UK was established by Akyaaba Addai-Sebo who came to the UK from Ghana and wanted to challenge racism and celebrate the achievements of black people in the arts, science and literature. People from African and Caribbean countries have been a fundamental part of our cultural heritage for centuries yet so often they have been unseen and unheard.

Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, Yinka Shonibare, Trafalgar Square 2010 -2012

I admit that the subject of black artists and black art was not something to which I had given much thought in the past. I was aware of the Nigerian British artist Yinka Shonibare from back in the days when I studied textiles, because of his extensive use of ‘African’ fabrics – actually Dutch wax print fabric that he sourced in markets in Manchester. These wax resist fabrics which are also known as Ankara, were inspired by Indonesian batiks, and were introduced to West and Central Africa by Dutch merchants during the 19th Century, the Dutch having colonised Indonesia. Shonibare uses the fabric in his work as a way of exploring colonialism and post colonialism, alongside issues of race and class. He is maybe best known for his scale replica of Nelson’s HMS Victory which graced the fourth plinth in Trafalgar square in London in 2010, the first artwork to reflect its setting within the Square. The ship’s 37 sails were made of Ankara to show African identity and independence, whilst considering the legacy of British colonialism and Empire, which was made possible through the freedom of naval trade routes opened up with Nelson’s victory in Trafalgar. The artwork is now permanently on display at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

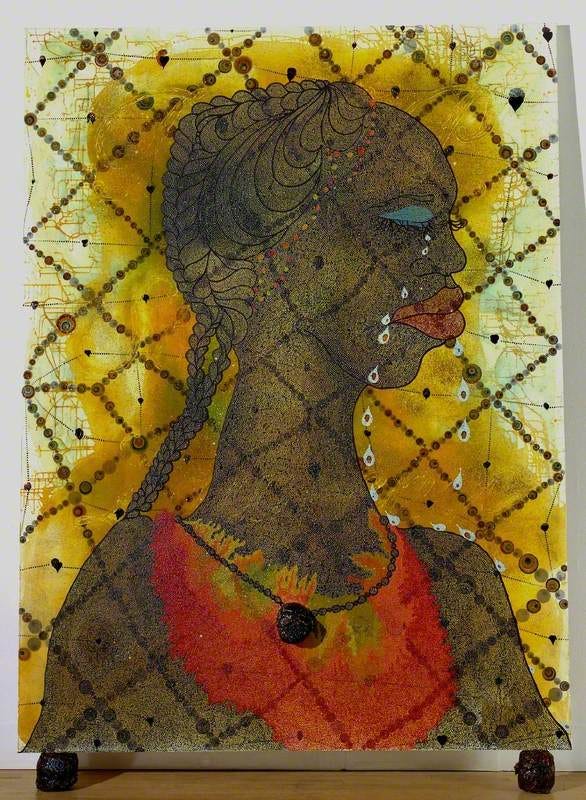

No Woman, No Cry, Chis Ofili 1998, Oil paint, acrylic paint, graphite, resin, paper, glitter, map pins and elephant dung, 2.43m x 1.8m

A commemoration of Doreen Lawrence, mother of murdered teenager Stephen Lawrence. In the painting Doreen is shedding tears, each bearing an image of her son

About the same time I had also seen a fabulous major retrospective of the work of Turner prize winner Chris Ofili at Tate Britain, whose exuberant layered paintings are known for their inventive use of media such as resin, beads, map pins, magazine cut outs, glitter and even elephant dung. But beyond this I couldn’t name any other Black artists, never mind Black female artists.

A couple of weeks ago I had a lovely day out in Cambridge with friend and fellow Substack writer

and we ventured to the Fitzwilliam Museum in search of art. We played at being art critics as we wondered how some paintings had come to be gracing the walls of such a major institution, agreed that Renoir wasn’t that great at painting faces whilst admiring some exquisite portraits by Gwen John and Vanessa Bell.The Dream, 2023 Pamela Phatismo Sunstrum, Crayon. pencil and oil on linen

But the single painting that really caught my eye was one of two black female figures holding eggs, symbols of rebirth and fertility, partially obscured by undergrowth. Painted by artist Pamela Phatismo Sunstrum, she describes the figures as alter egos allowing her to explore how people and cultures are embedded within a landscape, exploring ideas of colonialism and migration. I confess I do not fully understand how the painting achieves this, but I do know it was a totally captivating image drawing the viewer in to look closer.

The Dream (detail), Pamela Phatismo Sunstrum

At first glance the faces do not appear to be defined, but on closer inspection we can see that are there but not really visible, and it reminded me of another artist whose work explores visibility in minority groups, that I had seen at the Fitzwilliam earlier in the year. Back in January we visited a fascinating exhibition called ‘Black Atlantic’. I thought of writing about it at the time but as we saw it on the last weekend it was open, I decided against it. There seemed little point writing about something people would not be able to see and the moment passed. The exhibition told the story of what happened when European empires colonised the Americas and between 1400 and 1900 transported over 12.5 million people from Africa to these colonies. Twelve and a half millions slaves – just stop and think about that number, which is horrifying. Colonial enslavement affected every part of the Atlantic world. The exhibition specifically looked at how enslavement and empire shaped the Cambridge University museums, asking questions and discovering the stories behind the objects held, the people who collected them and how it all connects with global history. The exhibition featured several contemporary artists whose work allowed us to rethink these histories, hopefully creating better stories for the future.

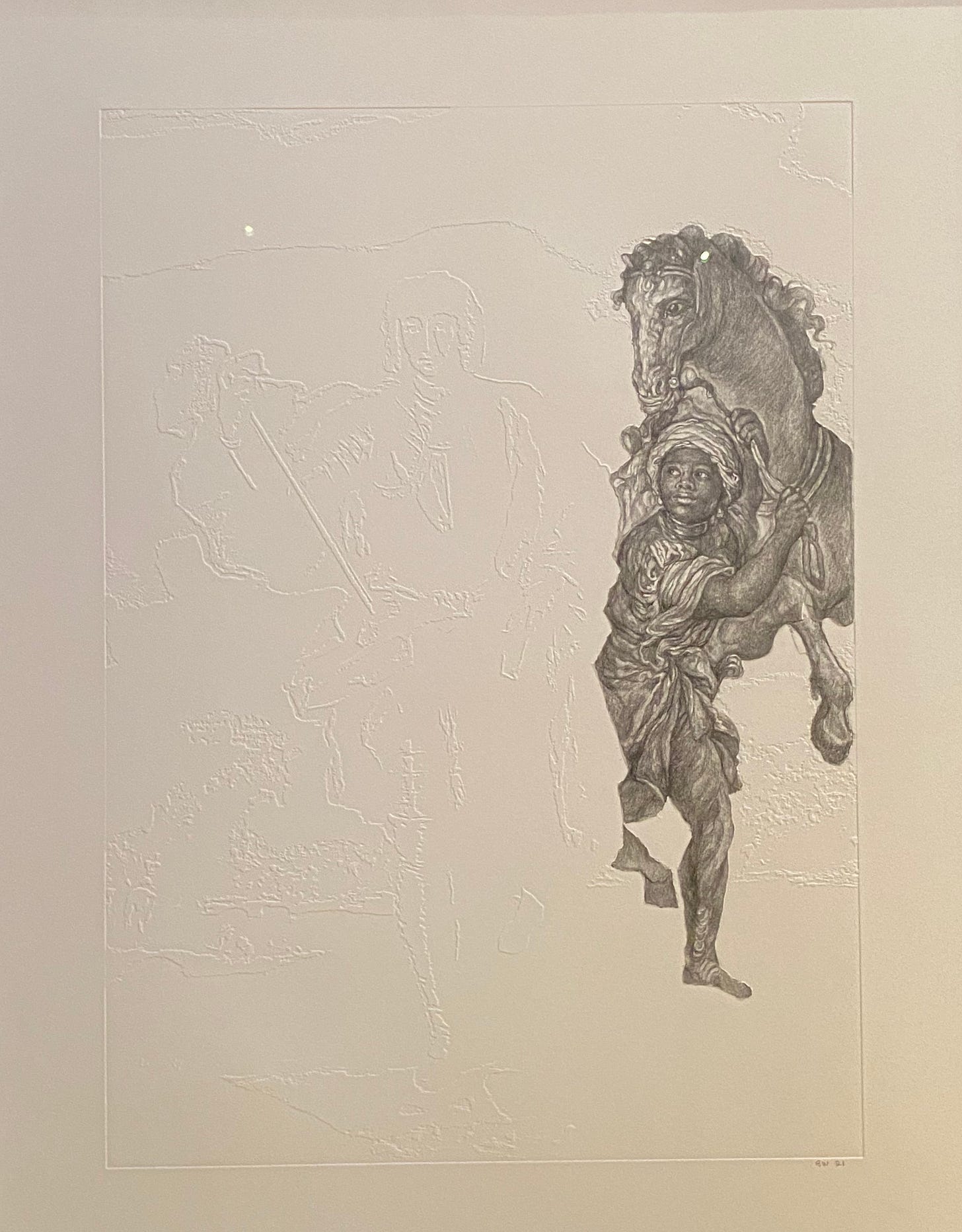

Vanishing Point 25 (Costanzi), 2021, Graphite on Paper, Barbara Walker

The one artist whose stunning work so eloquently explored the visibility of Black subjects was Barbara Walker, a British artist from Birmingham. Working in a variety of media from small scale drawings to large scale paintings she depicts people from minority groups, making them visible and giving them a voice. In a series called ‘Vanishing Point’ she takes European paintings from national and international collections, reworking them to alter the focus. She uses erasure as a metaphor for how the black community has been constantly overlooked, ignored and dehumanised by society. She takes these well known works and washes away, cuts out, isolates and diminishes certain aspects and figures within the image, giving emphasis to the black figures within each painting.

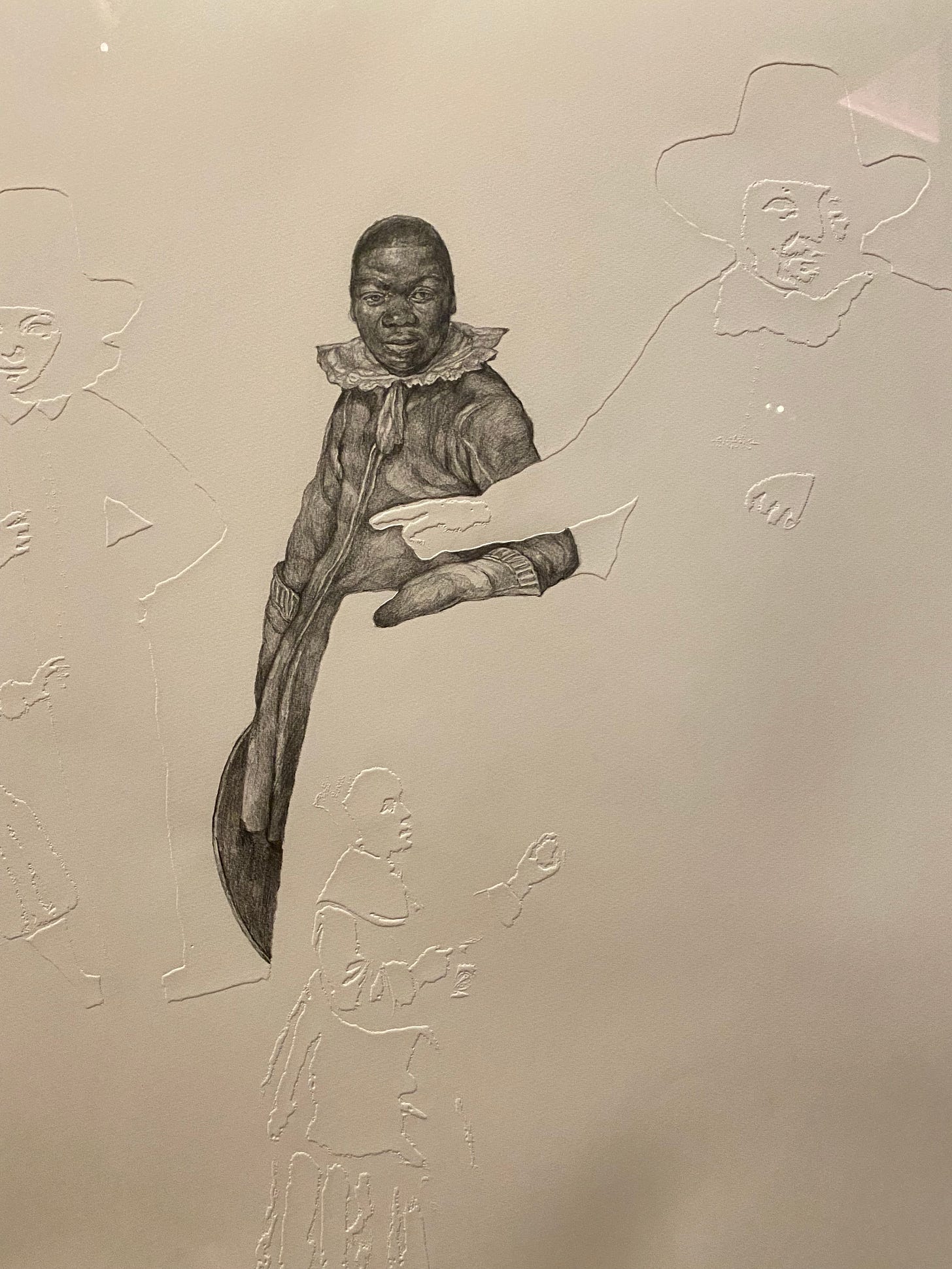

Vanishing Point 29 (Duyster), 2021, Graphite on Paper, Barbara Walker

I found her use of embossing particularly beautiful. Well known paintings are reproduced in white embossed paper with only certain figures drawn in graphite, reversing the conventional value placed on characters within the painting. No longer do we gaze on white men and women dripping in jewels and luxurious fabrics, wielding power and instead only the attendant black figures command our attention.

Making the Moment 3, 2022, Graphite on paper overlaid with mylar, Barbara Walker

A reworking of Portrait of Laura dei Dianti by Titian

In other works she reproduces the complete painting in a detailed graphite drawing but overlays it with tracing paper blurring the image except for small cut away sections, so once more we focus all our attention on the attendant characters.

I found the simplicity of these works so powerful in delivering their message.

“The function of Black art, as I saw it a few years ago, was to confront the white establishment for its racism, as much as to address the Black community in its struggle for human equality. I think that Black Art still has that role to play”

Eddie Chambers, artist, curator and historian, 1988

These words are just as true today as they were nearly 40 years ago and it is only if we confront the abhorrent racism within our history, no matter how uncomfortable, can we then learn and move forward to human equality.

Thank you for this post Gina. At age 89 and having lived for most of my life in Trinidad where I was born and the Uk. where I studied nursing in the late 50’s. I have now lived in Canada for over 60 years. DNA shows that I am 40% Nigerian and 60% white, primarily Scandinavian , Iberian and some Scottish and Irish, quite the mix. By some strange quirk I have never experienced racism in anyway. Only a few years ago I first heard about the Windrush generation. In school in the Caribbean. we studied only British and European history. Our educational system was based on the British system we learnt nothing about African or West Indian history. Black History never registered in my consciousness. I never thought much about black artists. I never related to being black. When I discovered that I was part Nigerian, I started taking an interest in all things Nigerian. I did not identify with the country but I became and still am a huge fan of Chiamanda Ngozi Adichie. Because of your post I am now very open to learning as much as possible about black artists, including artists from the Caribbean. Strangely enough in the Caribbean we tend too refer to ourselves as “mixed” rather than black as they do in the US. I believe in Africa they do not refer to their skin colour but rather as to their tribe. This is all very interesting and eyeopening to me on many levels. Thank you Gina as always for your very interesting and thought provoking posts.

Another interesting and well researched post Gina. Thank you for introducing us to these artists, the Barbara Walker drawings are quite exquisite, I had not heard of her before. I find the painting The Dream hauntingly beautiful, I actually wouldn't mind going back to look at it again, a little more carefully. I so admire you for visiting all the places you do, it makes me feel incredibly lazy! Thank you for the mention. x