As artists ultimately everything we do is all about storytelling, whether we write words, make paintings, compose music, or sculpt clay. We want to tell a story through our art because stories help us make sense of our world, distinguishing fact from fiction.

Objects are chosen in museums by curators to tell their part of the story in an exhibition or display. The labels that accompany these artifacts or works of art help to tell that story. They might just contain a title, with a note on materials used, the date it was made and the name of the artist. But sometimes there is also text written by the curator, which can have input from other contributors. These texts are usually written in the present tense to give the content more immediacy. They might tell us more about the context and how it contributes to the overall story, with additional information about the maker, drawing attention to different historical perspectives.

There is also usually a piece of summary text on the label which is known as ‘the tombstone’ which is presented more as a list rather than a piece of prose This is the factual information – the title, date, artist, institution, catalogue number, and who donated the piece.

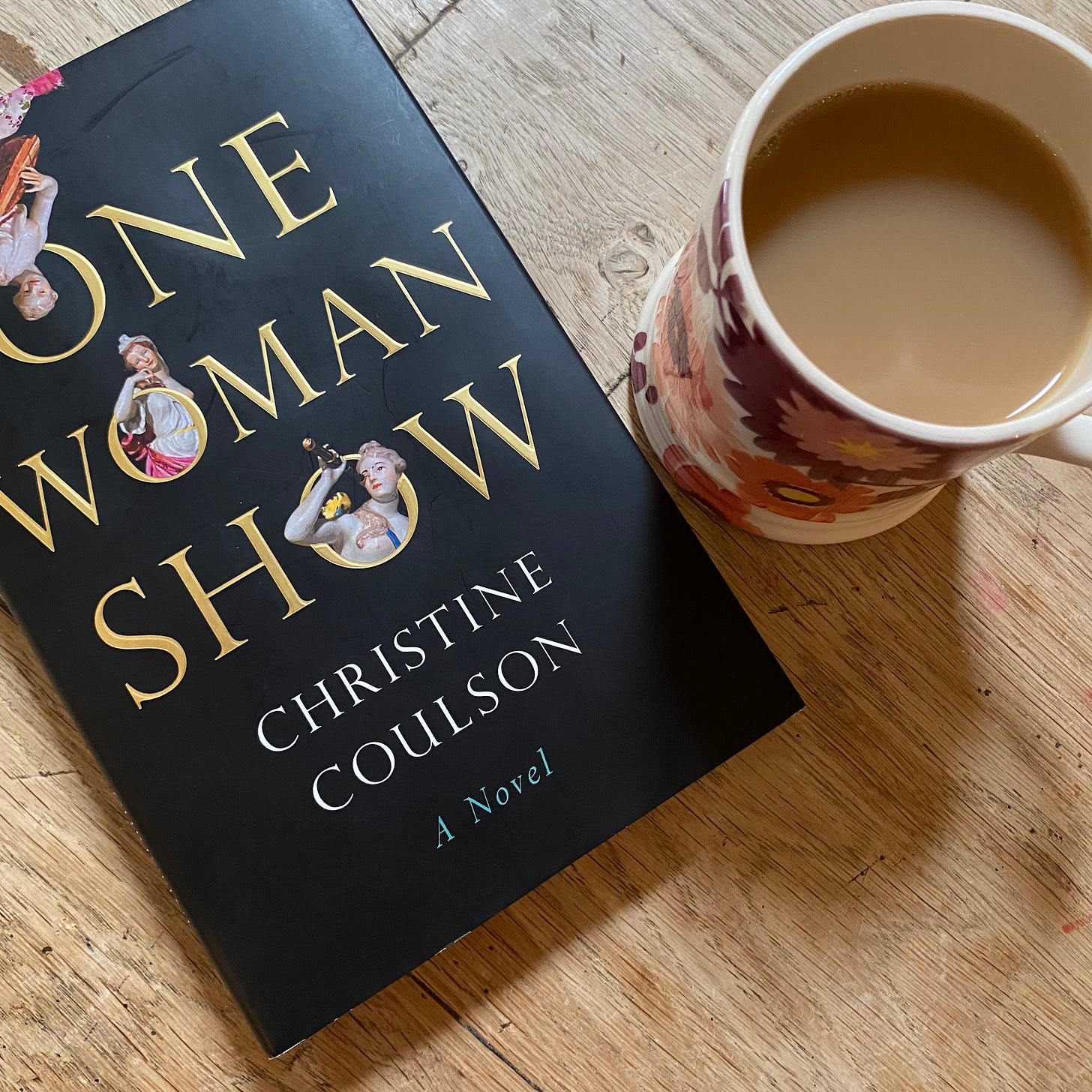

For example, earlier this year I visited a brilliant exhibition called ‘Black Atlantic’ at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, which explored the story of what happened when European empires colonised the Americas, transporting 12.5 million people from Africa to these colonies as slaves. Colonial enslavement impacted every part of the Atlantic world. The exhibition asked new questions about the objects held in museum collections that have been drawn from Atlantic enslavement. It looked at the people who collected these objects and donated them to museums, but more importantly it drew attention to the often overlooked stories of those who were enslaved. By resisting colonial slavery, people developed new cultures that continue to shape our world, cultures known as Black Atlantic, hence the title of the exhibition. It goes without saying that the labels in this exhibition contained powerful messages about each exhibit, telling this story of colonial enslavement. For example, this low relief ivory portrait was labelled as followed:

Ivory and Fashionable Portraiture

1700 The ivory carver David Le Marchand uses a piece of African elephant tusk, prized for its colour, workability and sheen, to carve this virtuoso low-relief portrait of the aristocrat Elizabeth Eyre. Neither patron nor artist probably consider how the heavy elephant tusks are transported on the backs of captive Black Africans to West African ports where both are sold as commodities

David Le Marchand (1674-1726)

Portrait medallion of Elizabeth Eyre (1659-1705)

1700 African elephant ivory

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge M.12-1846

Given by the Friends of the Fitzwilliam Museum, 1946

In this particular exhibition I felt the additional text enriched my experience, enhancing my understanding of the story being told. But is this always the case? It could be argued that too much detail, or in fact any information at all just distracts from the art it is describing. This was certainly the case for Jim Ede, which if you read my Substack last week, you will know he believed in displaying art without any labels. He wanted visitors to view the artwork in his gallery/home without any expectation or prejudice allowing them to form their own opinions, discovering new artists and work previously not considered. As a curator I imagine how much text, if any or whether you include a label at all, will depend on the story you are trying to tell through the art you are choosing to show because as I said at the start it’s all about the story telling. Which brings me on to a very interesting piece of story telling.

Author Christine Coulson worked for twenty five years, writing for the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Her final project at the museum was to write the wall labels for the museum’s new British Galleries. As part of her research and preparation for this, she read all the labels in all 400 galleries in the museum, loving all the nuances and variations. One of her favourites was the label that accompanied this portrait.

Federico Gonzaga (1500-1540)

The great Renaissance collector Isabella d’Este, marchioness of Mantua, commissioned this portrait of her son Federico Gonzaga to console her after he was taken to the papal court in Rome as a hostage. Francia based it on sketches he made of the ten-year-old heir as he was escorted through Bologna on his way to surrender himself. The painting, completed in just twelve days, captures a stylish youth with a gentle gaze and rosy cheeks that seem intended to convey purity and sweetness. Letters reveal that though Isabella was pleased with Francia’s work, the powerful matriarch thought Federico’s hair looked too blonde and sent it back so that the artist could darken it.

Title: Federico Gonzaga (1500-1540)

Artist: Francesco Francia (Italian, Bologna ca. 1447-1517 Bologna)

Date: 1510

Medium: Tempera on wood

Dimensions: overall 47.9 x 35.6 cm, painted surface 45.1 x 34.3 cm

Classifications: Paintings

Bequest of Benjamin Altman 1913

Accession no: 14.40.638

What a powerful story is being told here just through those few words. A story about a ten year old boy, who had his portrait painted as he was taken hostage… By the pope! And then his presumably grieving mother gave it back because the hair wasn’t quite the right colour? Was on earth was going on there? There are possibly more questions than answers on this particular label, which is just how it should be in all the best storytelling.

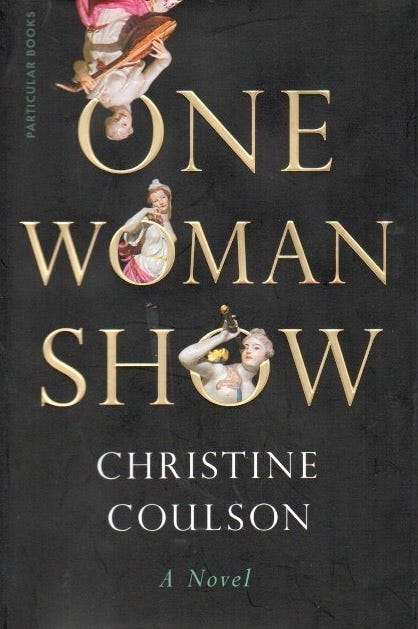

But where this particular example almost tells an entire story through a single label, Christine Coulson’s latest novel tells its entire story through a series of museum labels. Sticking to the format she used at the Metropolitan Museum of art, each label has the ‘tombstone’ information followed by a section of text no longer than 75 words. Not a single word can be wasted and each must be chosen carefully to convey just the right amount of information. For example, if writing about a silver teapot, she could tell you about the maker, the owner, the silver, the Rococo form, the history of tea making in 18th century London, the relationship of tea to the slave trade etc. Any of these things could tell a story about the teapot but the limited format does not allow all of these things to be told. The curators job is to choose what stories to tell through the label, to point out what they think is most important or significant, in words that can be understood. Just as in the Francesco Francia portrait above we don’t need to know everything to understand the story.

“The most important part of a story is the piece of it you don’t know.”

Barbara Kingsolver, The Lacuna

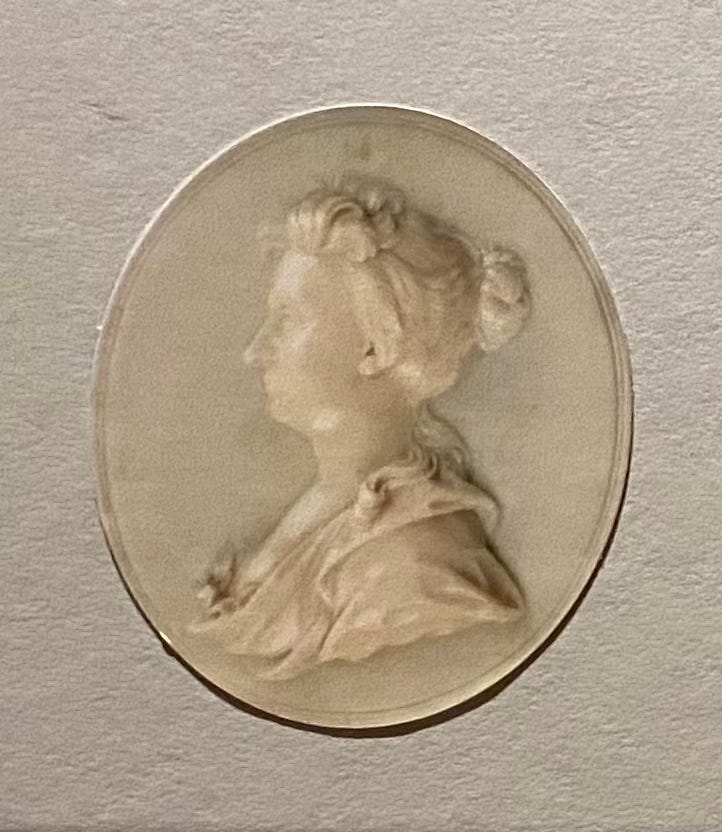

In ‘One Woman Show’ Christine Coulson tells the story over the course of a century, of protagonist Kitty Whittaker, almost entirely through museum labels describing her as if she were an artifact on display. Born at the beginning of the twentieth century, the novel charts Kitty’s life as she moves from ‘collection to collection’ from her parent’s ownership to that of various husbands. Each stage of her life is distilled into a brief snapshot, giving an insight into the ownership, value and power of women. It is an incredibly clever, interesting concept that enhanced my understanding of museum labels, and it is beautifully crafted, but I’m not entirely sure I enjoyed it. How much of that was down to me not particularly liking Kitty and her social set (which put me in mind of The Great Gatsby, a book which I didn’t enjoy at all) I’m not sure. However, given the format of a single label per page it was quick to read, in a single sitting, so it wasn’t arduous. It felt more like a very short novella than a novel.

It is both poignant and witty in places and Kitty emerges as an eccentric heroine flawed with human foibles. You actually feel the raw pain of her numerous miscarriages, which she copes with through her lifelong propensity for kleptomania. Coulson poses the interesting question of who gets to write our stories? If you can borrow a copy then I would say it is worth reading for both the novelty of style and the exquisite economy of language, but I’m not necessarily recommending that you go out and buy it. I’ll leave you with one of my favourite labels, that in just a few words perfectly describes Kitty’s life of dieting, restraint and discontent.

Tuna Salad on White Toast with Carrot Sticks

Lunch, 1950

Collection of William Poll Speciality Food & Catering

1051 Lexington Avenue, New York City

A rectilinear composition of four diminutive sandwich triangles punctuates a circular porcelain plate in an abstract portrait of calorific constraint. Three orange stripes, peeled carrots of limited dimension, add to the Mondrian rigour, drawing the eye without tempting the palette. Kitty eats this still life alone and with the quiet resolve of a squirrel unable to temper the determined lust of its consumption. A cigarette follows.

- One Woman Show, Christine Coulson, 2023

Sounds a fascinating way of telling a story, even if you didn't like the people. Unfortunately my library doesn't have any copies yet, maybe when it comes out in paperback