The stories of Charles Dickens are so universally familiar I just assumed that at some point in my life I must have read his work. But now I am starting to think that my familiarity derives from other sources of popular culture rather than the actual novels.

I grew up to the soundtrack of the wonderful 1960 Lionel Bart musical ‘Oliver” in both screen and stage versions with all its iconic songs. I was fortunate to see Robert Lindsey play Fagin in a wonderful version at the London Palladium many years ago and I have also played the part of the Artful Dodger in a pantomime version of the story called “A Tale with a Twist”.

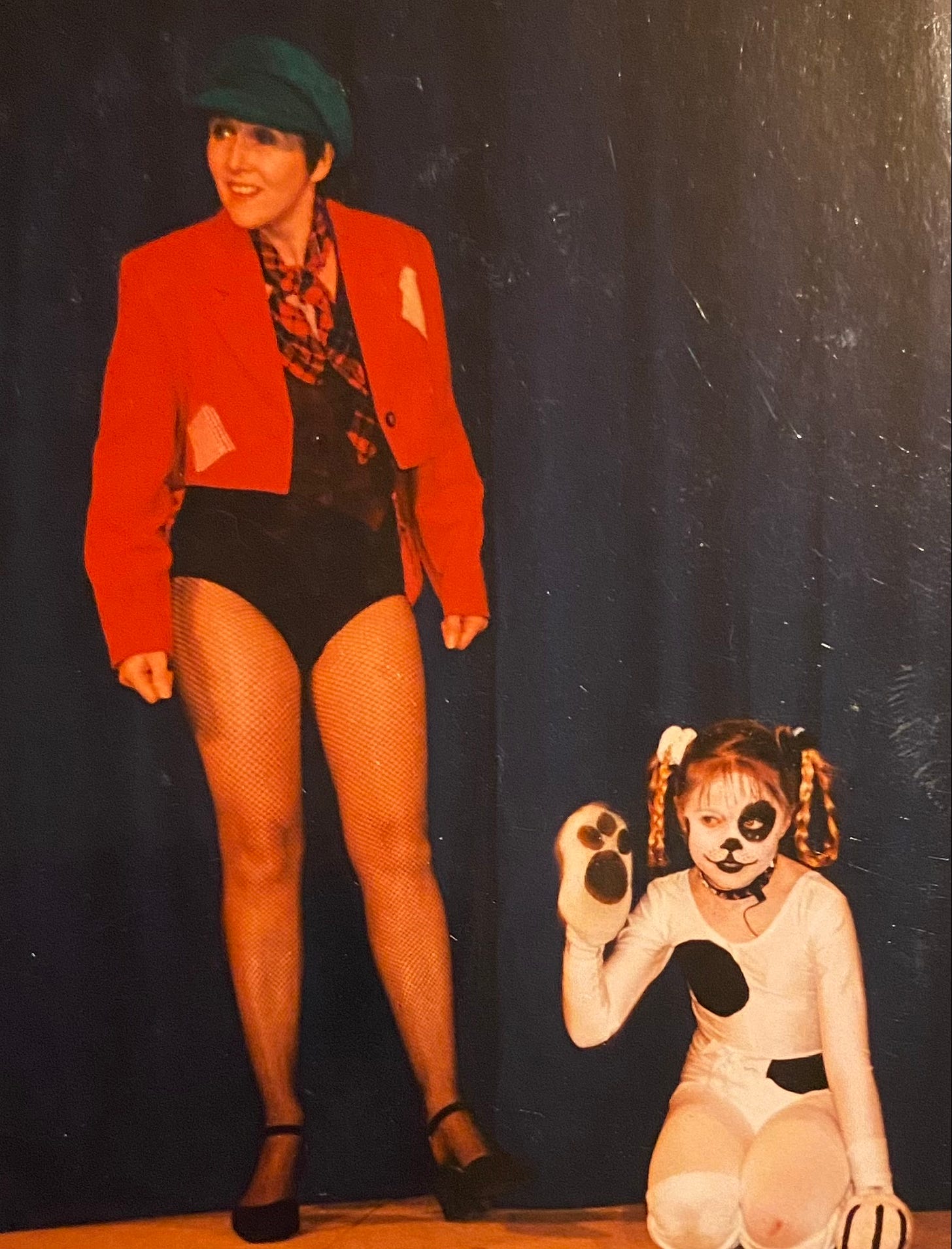

“Dodger and Bullseye” in Tale with a Twist… circa 25 years ago!

Not the most obvious story as the basis of a Panto plot but that’s Amdram for you. I loved the 2019 satirical film “The Personal History of David Copperfield”, as well as other various other TV adaptations and of course the endless retellings of A Christmas Carol (my top vote goes to the Muppets) which are synonymous with the festive season have all led me to believe I have read Dickens and not only read his work but extensively. However I’m starting to have a sneaking suspicion that I never have.

But I will back track a little. Being both an enthusiastic reader and a keen knitter, for quite a while I have pondered on the appearance of knitters in literature.

In the Harry Potter series, Mrs Weasley knits a sweater for each of her seven children plus Harry every single Christmas, which I think is rather an astonishing feat and it makes me think that J K Rowling probably isn’t a knitter herself. Despite this Mrs Weasley isn’t the only knitter in the series and Hermione Granger takes up knitting hats, badly as it happens, and Hagrid also knits on a train journey with Harry to Diagon Alley

“Hagrid took up two seats on the train and sat knitting what looked like a canary-yellow circus tent”

Philosopher’s Stone (Book 1) by J K Rowling

The March sisters knit in Little Women although it’s not a popular activity with Jo who proclaims:

“I can’t get over my disappointment at not being a boy and it’s worse than ever now for I am dying to go and fight with Papa, and I can only stay home and knit, like a poky old woman”

Jo March in Little Women by Louisa May Alcott

Another famous literary knitter is Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple who sits knitting whilst astutely observing the goings on around her and analysing the clues to the latest mystery, in every way just as sharp as her needles.

“Sitting here with ones knitting, one just sees the facts”

Miss Marple in The Blood Stained Pavement by Agatha Christie

But probably the most famous knitter of all is Madame Defarge In Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities which has led me to wonder if I have actually read any Dickens before. Whilst I was familiar with Oliver Twist and Great Expectations etc, I knew I had never read A Tale of Two Cities, the story of the French Doctor Manette who has been imprisoned in the Bastille in Paris. On his release he goes to live in London with his daughter Lucie whom he has never met but events take a turn, and they end up back in Paris against the backdrop of the Reign of Terror and the French Revolution. However, despite never having read it there was a copy of the novel on my shelves, part of a collection of classics, most of which I have never read.

Knitting on my mind… My 2025 project The Jenny Jacket by PetiteKnit

I decided it would be a good idea to redress this gap in my knowledge of classical literature and maybe try to read a few of these books this year, so with knitting on my mind I picked A Tale of Two Cities off the shelf. I didn’t get far before I realised that despite being very familiar with so many of the stories and characters I could never have read any Dickens before because I would have definitely remembered. My goodness he is so verbose! Why say something in a couple of sentences when you can spin it out to a couple of pages or more.

And the man does love a metaphor, eking out every last drop possible. (The pun is intentional.) In describing the crowds during the storming of the Bastille, he likens the masses to a sea of people, literally in every conceivable way.

“As a whirlpool of boiling waters… the living sea rose, wave on wave… and overflowed… the furious sound of the living sea… the force of the ocean bearing on him… as if he had been struggling in the surf of the south sea… the sea that rushed in…. the living ocean…leaped into the air like spray… surging and tossing… the sea of black and threatening waters… wave against wave whose depths were unfathomed… the remorseless sea… the ocean of faces.”

I’m sure you get the picture!

But I also found it very funny in places with the most wonderful descriptions, and let’s face it, it’s hardly a funny book… people are getting their heads chopped off left, right and centre.

But returning to the reason I chose to read this novel and that is Madame Defarge. She is a minor character yet a significant one, representing the extreme presence of the Revolutionaries. She is bloodthirsty and vengeful and towards the end of the book we discover the reason for her extreme hatred of the aristocracy is down to the Evrémonde family who are responsible for the rape and murder of her sister and murder of her brother. Throughout, whenever we meet her she is never without her knitting. We encounter her early on as the wife of the wine shop keeper, sitting behind the counter of the shop, a stout woman aged around thirty with a watchful eye and composed manner. She has large heavily ringed hands and is wrapped in in fur with a shawl around her head, allowing her large earrings to be visible. We can sense a strong character blessed with the courage of her convictions.

“Her knitting was before her, but she had laid it down to pick her teeth with a toothpick… she then took up her knitting with great apparent calmness and repose of spirit, and became absorbed in it.”

A visiting gentleman to the shop notes:

“You knit with great skill, madame.”

“I am accustomed to it”

“A pretty pattern too!”

“You think so?” said madame, looking at him with a smile.

“Decidedly. May I ask what it is for?”

“Pastime,” said madam, still looking at him with a smile while her fingers moved nimbly.

“Not for use?”

“That depends. I may find a use for it one day. If I do… well… I’ll use it.”

But by now we know that what she is doing is encoding the names and crimes of aristocrats, including the gentleman in question, into the fabric of her knitting, composing a register of the names of those who are destined for the guillotine

“Knitted in her own stitches and her own symbols, it will always be as plain to her as the sun.”

Madame Therese Defarge is of course entirely fictional, but Dickens modelled her on Les Tricoteuses, the French women who sat and knitted in front of the guillotine.

Contemporary depiction of Les Tricoteuses by Jean-Baptiste Lesueur

In the second half of the eighteenth century the market women of Paris were the backbone of society. They worked, traded, ran their households, brought up their children whilst all the while knitting and sewing to clothe themselves and their families. When the situation grew so dire they could no longer feed their families they rebelled, famously marching on Versailles in October 1789, which became the trigger to the French Revolution. The women played a crucial part in the Revolution, forming groups, marching the streets of Paris demanding the arrest of the wealthy. Female leaders of these groups were invited to observe the National Convention which was the first assembly to govern France during the Revolution. Before long the governors felt threatened by these women and their rising power, and they were banned from the meetings and forbidden to take part in any political assemblies.

In protest, some of the women took up places at the Place de la Revolution (now Place de la Concord) the site of the executions. They brought along chairs and sat themselves around the guillotine in ringside seats, knitting while they watched the heads rolling. Because it was a public square and the public were encouraged to witness the executions, the government were unable to prevent the tricoteuses from taking up their prime positions. The women soon began to sell their seats as well as selling the mittens, socks and scarves that they knit so in this way the tricoteuses were able to continue to support their families. In particular they also used to knit the red bonnets or Liberty caps worn by the Revolutionaries. This type of cap also known as a Phrygian cap, a conical brimless hat with a crown that folds over to the front or side, has been worn for centuries since antiquity as a symbol of liberty and freedom. They were adopted by the French Revolutionaries during the Reign of Terror as a sign of allegiance, to be worn by anyone, including aristocrats, who wished to avoid the guillotine.

The red liberty cap or ‘Bonnet rouge"‘

It was unlikely that the majority of these women were able to read or write so the likelihood of them knitting code into their work is not very high, but I didn’t have to dig very far to discover where Dickens might have developed the idea of Madame Defarge using knitting as a coded messaging system. Charles Dickens moved in the same social circles as the inventor of the first computer Charles Babbage and the mathematician Ada Lovelace, frequently attending the same dinner parties. Dickens is even said to have read a passages from his books to Ada on her deathbed. And these friendships probably meant he was no stranger to the idea of coded binary messages. Given that knitting is a form of binary activity consisting of just two types of stitches – knit or purl, it doesn’t take a huge leap to see how he envisaged Madame Defarge knitting a coded register of names.

Madame Defarge continues to knit throughout the book and on every occasion we meet her whether it’s sitting behind the counter of the wine shop or standing outside leaning against the doorpost she has her knitting to hand, constantly observing and recording. That is until we approach the denouement. Here Defarge hands her knitting to her lieutenant requesting her to “have it ready in my usual seat” in the Place de la Revolution, before she heads off on a deadly mission, which (spoiler alert) doesn’t end well for our revolutionary knitter. She never does return to her knitting.

First completed project of 2025. A pair of socks for me. Parade by Judy Kaether

Despite the overly garrulous style I enjoyed the story overall, although I can’t see me rushing to read more Dickens any time soon. But I would love to hear any recommendations you might have where knitting plays a part in the narrative of a novel.

So many thoughts! Firstly - an admission - I love Dickens and I thoroughly urge you to rethink reading other works by him. My favourite - and in my opinion one of the best novels ever written - is Bleak House. His style is definitely overblown but his verbosity was a shrewd move for a writer getting paid by the word and sometimes some skimming is called for!

As a knitter, I found your section on the tricoteuse intriguing. Thanks for the insight. My father had been so spooked by them as a child that he always brought them up unfavorably when my mother was knitting! Whether they used their work to encode messages does seem far fetched but in Early Modern times various elite ladies such as Mary Queen of Scots used their embroidery to send secret messages so it is at least a thought, It also made me think of all the (admittedly to me unknown) meanings of the Arran patterns in sweaters - including the deliberate mistake made in each to identify the owner if they were lost and sea and their body washed up and was unrecognisable.

If you hear of any other good books featuring knitters or knitting - let me know,

I’m not a big Dickens fan but I’ve read quite a few of his novels. I find it takes a few chapters to get into the rhythm of his writing and then it rolls along quite readily. Bleak House is a favourite. I think there are some ‘light’ knitting novels out there - crime fiction mostly- and I have a book called Knitting Yarns which is a compilation of short stories involving knitting.