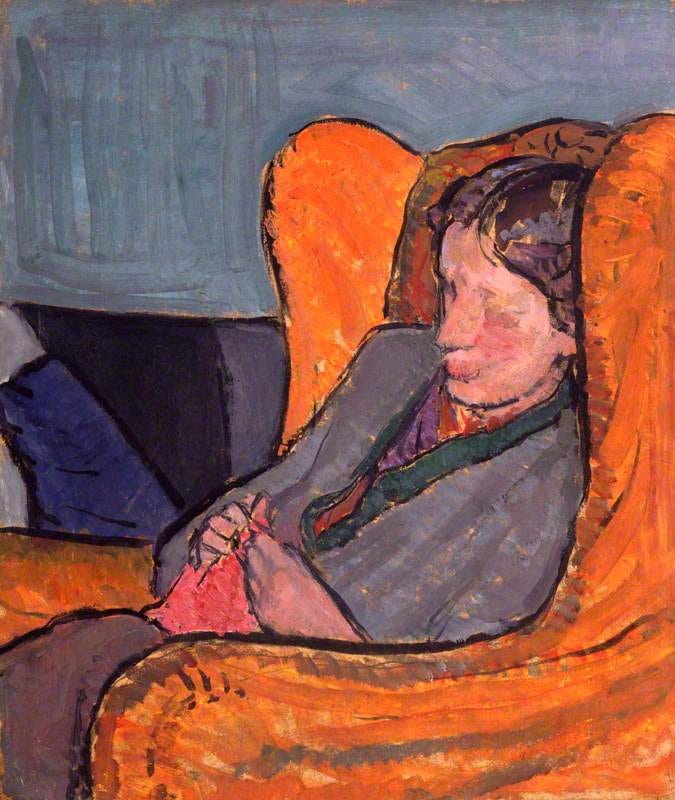

One of my favourite paintings is one that I have featured here only a couple of weeks ago – a sensitive intimate portrait of Virginia Woolf sitting in an armchair knitting, painted by her older sister Vanessa. Yet aside from that painting which I seek out whenever I get to visit the national Portrait Gallery, I was until recently largely unfamiliar with the work of Vanessa Bell, despite her being a key figure in the Bloomsbury Group. But last week we drove over to Milton Keynes to the largest ever exhibition to focus on Bell’s work, Vanessa Bell: A World of Form and Colour.

Virginia Woolf by Vanessa Bell, Oil on board, 1912, National Portrait Gallery

Vanessa and Virginia were born into a wealthy liberal literary family in the latter part of the 19th century, Vanessa being the eldest of four siblings. The family also included a half-sister and two half-brothers. Her father Sir Lesley Stephen was an author, a philosopher, and a humanist who believed that women ought to be as well educated as men.

“I hate to see so many women’s lives wasted simply because they have not been trained well enough to take an independent interest in any study or to be able to work efficiently at any profession” Sir Lesley Stephen

The family lived in South Kensington where Vanessa studied art first in Kensington with Arthur Cope a British portrait painter and latterly at the Royal Academy under the tutorage of John Singer Sargent. Her Mother died in 1895 when Vanessa was only sixteen and by age twenty five her father also died leaving her alone with her younger siblings. The family left Kensington and moved together to an unfashionable area of Bloomsbury, where she set up home rejecting the lingering Victorian attitudes of the time and adopting a new radical way of living. The unconventional lifestyle was one she continued to live her entire life. She established what became known as the ‘Friday Club’ a progressive gathering for artists and writers where men and women could work and exhibit together. It was here that she met other creatives, including her husband Clive Bell as well as her long-time partner the artist Duncan Grant, and collectively they became known as the Bloomsbury Group.

Girl Drawing by Vanessa Bell, Oil on canvas, 1932, Charleston Trust

She travelled extensively, especially in Italy where she became acquainted with the work of the Old Masters and to Paris where she discovered the avant-garde. By 1912 she was exhibiting paintings alongside artists such as Matisse, Picasso, Derain and Braque at the second post-Impressionist exhibition. In 1913 she co-founded the Omega workshops with Duncan Grant and the critic and painter Roger Fry where they created modern furniture, textiles and ceramics in an attempt to challenge the division between applied and fine art, applied art having always been considered the lesser of the two. Dabbling with these ‘lesser’ arts was seen as transgressive yet it opened Bell up to pattern and abstraction, line and colour, giving a freshness to her work. At about this time Bell also started to experiment with abstract art, never being afraid to embrace new ideas and this pushed her to the forefront of experimental artistic movements. Although she soon moved away from working in the abstract she retained an interest in simple shapes and bold colour as can be seen in the work ‘A Conversation’. It is a painting of three women pictured in front of a window, so engrossed in conversion they are oblivious to the garden of colourful flowers outside.

A Conversation by Vanessa Bell, Oil on canvas, 1913-16, The Courtald Gallery

At the start of the first world war Vanessa and Clive Bell, Duncan Grant and Duncan’s lover David Garett all moved to East Sussex and settled in Charleston farmhouse which allowed the men to do farm work which was required of them as conscientious objectors. Vanessa and Clive had an open marriage both taking lovers and as well their own two sons Clive also raised Vanessa’s child Angelica, whom she had with Duncan Grant.

Virginia Woolf by Vanessa Bell, Oil on panel, 1912, National Trust’s collections Monk’s House

After the war Vanessa once again travelled extensively, renting a house on the Côte d’Azur, a French version of Charleston which became their summer haven until the outbreak of the second world war. Back at Charleston, Bell and Grant began an ongoing project to decorate the walls and furniture throughout the house, which became a radical artistic retreat for various artists and their friends including the writers Lytton Strachey and E. M. Forster. At this time as well as painting, Bell and Grant were receiving commissions to decorate society homes and Bell also designed dust jackets for books published by Hogarth Press set up by Virginia and Leonard Woolf, which included all her sister Virginia’s novels.

Interior with the Artist’s Daughter by Vanessa Bell, Oil on canvas, 1936, Charleston Trust

The exhibition in Milton Keynes shows a wonderful variety of work from Vanessa Bell, produced throughout her entire life. The paintings demonstrate how she was always open to innovation and that she did not fear change. She dabbled with abstraction, tried out collage and played with pointillism, calling it painting in a ‘leopard manner’ but it was her beautiful realistic interiors and portraits that attracted me the most. They have a clarity of style and an intimacy that draws you into her domestic world. Her close observations of a sitter reading, writing, sewing or knitting cannot help but pull you into the room with them.

Portrait of Molly McCarthy by Vanessa Bell, Oil on panel, 1912, Private Collection

One of the other highlights of the exhibition as well as the paintings and some examples of the decorative work at Charleston was a display of fifty dinner plates.

The Famous Women Dinner Service by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, 1932, Ceramic, The Charleston Trust

After the closure of the Omega Workshops Bell continued to produce textiles and decorated ceramics with potters such as Clarice Cliff and her son Quentin Bell. In 1932 she and Grant received a commission from the art historian Kenneth Clarke to create a dinner service that included fifty decorated plates that celebrate women throughout history. On each plate is a portrait of a different woman from history or myth, plus one man, Duncan Grant.

All fifty plates from the ‘Famous Women Dinner Service’ are on display at the exhibition, each one in incredible condition yet this wonderful body of work was apparently kept in obscurity until 2018 when it passed from a private collection and was put on display at Charleston, which is now a cultural centre. They have been described as one of the great overlooked works of feminist art and I tend to agree. They were fascinating and have left me with a desire to decorate a plate or two, although probably not fifty! They also made me think of the 1979 installation work ‘The Dinner Party’ by the American feminist artist Judy Chicago which is also designed to showcase and honour women from throughout history, except I now know that Vanessa did it first.

The Dinner Party by Judy Chicago, 1979, Thirty nine place settings each representing a woman from history featuring a hand painted plate, ceramic cutlery and chalice, a napkin and its own unique embroidered runner, Brooklyn Museum New York.

Many unhappy events occurred in Vanessa’s life during the ten years from 1934 including the deaths Roger Fry, her son Julian, her sister Virginia and her friend John Maynard Keynes. Her studio and much of her early work was destroyed by a bomb during the war and then in 1944 she developed breast cancer. Yet despite these setbacks she continued to travel, paint and exhibit widely up until her death in 1961.

Self Portrait by Vanessa Bell, Oil on canvas, 1958, Charleston Trust

Much of the work from this period is set in and around Charleston and features still lives and portraits of her family and friends. More of the intimate domestic settings that I found so appealing. The exhibition is open until 23rd February and if you get a chance I would definitely recommend going to see it.

So interesting about the dinner service. I wonder if Judy Chicago had ever heard of it? We absorb things without awareness.

When you do get to Charleston, you’ll love it all the more for finally getting there.

Thank you for the information and putting the pictures into context. I met with a friend last week, she had been to the exhibition and highly recommended I go. Which I will do before it changes.